|

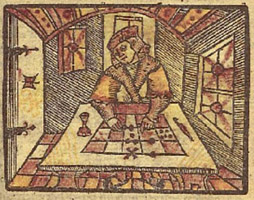

From the 13th century the so-called calculating on the lines became more and more popular in Europe and finally replaced Gerbert abacus entirely. Here are the requirements for this method:

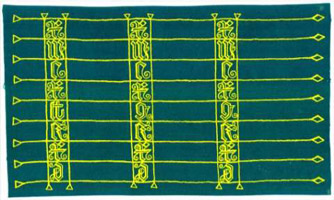

a plane surface with straight lines drawn with equal intervals which are parallel to the edge of the surface. This edge is just the opposite to a counting man who uses

jetons. On the first line closest to a counting man a jeton is equal to one. On the second line a jeton is equal to 10, on the third line it is equal to 100.

A jeton placed on the interval between the first and the second lines is equal to 5. A jeton placed on the second interval is equal to 50 and so on. A special table,

a piece of cloth: a shawl or a rug, and later a sheet of paper were used as a plane surface. A special branch of industry was developed to produce metal jetons

especially flourished in Nuremberg, in the 16th – 17th centuries.

A special methods for each arithmetical operation were developed. Different authors have suggested a lot of ideas how to calculate on the lines, but in common they

were similar. Often these ideas depended on peculiarities of a local financial system. Treatises on calculating on the lines were still being published even after a “pen and paper" calculation method appeared. Up to the 16th century many textbooks were still comparing these two methods.

|

|

|

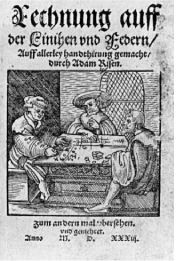

Arithmetics of Balthasar Licht (1500), Johann Booschensteyn (1514) and Adam Ries (1574)

|

Jetons for calculation (augrim stones) are mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in “The Canterbury Tales”. William Shakespeare mentioned them in his “The Winter's

Tale” - he called them counters. Also J.-B. Moliere (1673) wrote about calculating on the lines with jetons. It is known that Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz preferred to count with the help

of jetons. A calculating on the lines method was spread all over Western Europe. It was used up to the end of the 18th century, when it was finally replaced by calculations with

pen and paper.

|